Plant Life

Grasslands

intermountain prairie into nonnative plant communities through agricultural modification, introduction of exotic plants, and urban development. The native prairie ecosystems once comprised mid-length perennial grasses and wildflowers that supported diverse mammals, birds, insects, and other organisms that recycled organic matter into fertile soil.

Figure 2.38: Mission Valley. Source: Lori Curtis

In some areas, conifer trees have expanded onto the land where grasslands once dominated. Smaller grasslands and meadows appear in the South and North Forks of the Flathead and the Swan valleys. Some native grasslands remain protected in Waterton Lakes National Park, in the North Fork of the Flathead in Glacier National Park, in the National Bison Range, on Wild Horse Island State Park, and in the Dancing Prairie Preserve north of Eureka. Grasslands support a variety of mammals, reptiles, birds, and insects. In parts of the Mission Valley, prairie grasslands are dotted with wetlands increasing their ecological significance.

Wetlands & Riparian Habitat

The Flathead Watershed has some of the most diverse assemblages of wetlands in the Rocky Mountains. These include peatlands, oxbow ponds, springs, seeps, pothole pond complexes, vernal pools, and beaver ponds, each contributing to the watershed’s high biodiversity and functionality. Wetlands perform valuable functions such as flood water retention, sediment trapping, and water filtration. They provide habitat for resident and migratory birds as well as insects, fish, amphibians, and reptiles. Many mammals depend on wetlands for their survival, including moose and beaver. These areas are dominated by alder (Alnus), aspen (Populus), cottonwood (Populus), dogwood (Cornus), willow (Salix), hawthorn (Crataegus), cattails (Typha), sedges (Carax) and meadow grasses.

Riparian habitats occur in high and low elevation valleys and low slopes in long sections beside streams and rivers. The word “riparian” refers to a vegetated area associated with moving and still water systems. They occupy the area between land and rivers or lakes, and are usually transitional between wetlands and uplands. Riparian areas either have distinctly different vegetation than adjacent areas, similar but more robust vegetation, or both. The continuous availability of water in these areas provides a unique environment for moisture-loving species such as wetland shrubs.

|

|

| Figure 2.39: Deciduous wetlands. Source: Amy Chadwick, Watershed Consulting | Figure 2.40: Willows/sedge wetlands. Source: Amy Chadwick, Watershed Consulting |

At lower elevations, riparian areas also support Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), Rocky Mountain juniper (Juniperus scopulorum), aspen (Populus tremuloides), western paper birch (Betula papyrifera), and black cottonwood (Populus balsamifera ssp.). Douglas-fir, Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmanni), lodgepole pine (Pinus contoria), ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), the shade-intolerant western larch (Larix occidentalis), and western white pine (Pinus monticola) are present at higher elevations. Shade tolerant species such as grand fir (Abies grandis), subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), and western red cedar (Thuja plicata) occasionally dominate. The understory shrubs found in these habitats include alder (Alnus), birch (Betula), dogwood (Cornus), and snowberry (Symphoricarpos). Riparian forests, shrublands and meadows provide critical habitat for wildlife and play a significant role in maintaining water quality, water quantity, and the stability of streams.

|

| Figure 2.41: Western larch. Source: USDA-NCRS |

There are two types of trees: coniferous (needle- or scale-leaved, cone-bearing, mostly evergreen) and deciduous (seasonally lose their leaves). Both types are found in the forests of the Flathead Watershed. Western larch (L. occidentalis) is a deciduous conifer. These trees differ from all other native conifers that retain their foliage throughout the winter. In fall the forest is sprinkled with stands of golden trees. When the needles fall, they line the roads much like those of other leafy deciduous trees, floating up as vehicles pass by, then settling into a glowing, inviting path on either side of the road. Altitude, temperature, and moisture dictate which trees grow where in the watershed forests. A large forest—diverse in species, age, density, and understory—defines the other species that live within it.

Trees provide valuable ecosystem functions throughout their lives. Each individual tree has the potential to supply food and homes to a variety of animals, and a group of trees can also provide shelter, wind breaks, and soil protection. Tree bark offers homes for invertebrates that in turn provide food for birds and small mammals. Fallen trees (also called nurse trees) create habitat for mammals, invertebrates, fungi and mosses, and eventually decompose into complex soils that support continued plant life. Many local forests also provide a diverse array of important wood products while sustaining the forest products industry.

|

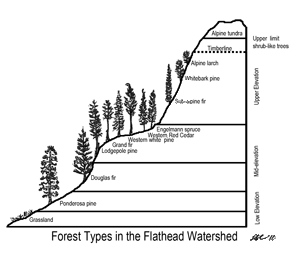

| Figure 2.42: Forest Distribution. Source: Adapted by Lori Curtis |

Low- to mid-elevation montane forests are dominated by Douglas-fir (P. menziesii), lodgepole pine (P. contoria), and western larch (L. Occidentalis). Western red cedar (Thuja pilcata) tends to grow in the warmer, wetter forests and ponderosa pine (P. ponderosa) grows in the drier and more southerly environments. Shrubs such as mountain alder (A. incana), huckleberry (Vaccinium globulare), ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius), mountain maple (Acer glabrum), and berry producing shrubs make up a diverse low- to mid-elevation understory. Arnica (Arnica), aster (Aster), bunchberry (Cornus canadensis), glacier lilies (Erythronium grandiflorum), lupine (Lupinus), paintbrush (Castilleja species), and pine grass (Calamagrostis rubescens) are common in these forests.

|

| Figure 2.43: Indian Paintbrush. Source: Blackfoot Native Nursery |

The colder subalpine forests have shorter growing seasons and amass greater snow accumulation. These forests support lodgepole pine most dominantly, as well as Engelmann spruce (P. engelmanni), and subalpine fir (A. lasiocarpa). Beneath the trees grow false huckleberry, huckleberry (V. globulare), glacier lilies (E. grandiflorum), Oregon grape (Mahonia repens), kinnickinnick (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), and beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax). In the higher elevations, the canopy is more open and additionally supports whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) and sub-alpine larch (Larix lyallii), which are often dwarfed by harsh weather.

Avalanche chutes are fairly abundant on the precipitous slopes of subalpine forests. Fast moving avalanches periodically scour the landscape, removing trees from the mountainsides and exposing grasses, forbs, and shrubs to the sun’s energy. Avalanches are a critically important natural process that opens chutes of vegetation to provide nutrient rich foods for browsing mammals, including grizzly bears.

At and above about 7,000 feet (2,100 m), and with average summer temperatures below 50°F (10°C), the alpine region (alpine tundra in B.C.) at the 49th parallel supports no trees. As a general rule, treeline decreases as latitude increases. To someone from Mammoth Lakes, California (at a latitude just over 37°), the Flathead Watershed treeline would be considered low, while someone from Fairbanks, Alaska (at a latitude just over 64°) would consider it high. The growing season is short in the alpine region, but lengthy summer days promote the growth of a variety of plants. Mountain heather, mountain avens, and other wildflowers carpet the hillsides, as do low-growing, long-living cushion plants. Even in dry rocky areas, primitive and resilient lichens grow extensively.

|

| Figure 2.44: Tree snag with nest. Source: Lori Curtis |

Old growth forests provide important habitat elements for mammals, birds, amphibians, fish, invertebrates, mollusks, fungi, and lichens. Most notably they provide excellent homes for cavity nesting birds. Their features include snags (dead-standing trees often missing their tops), decaying trees, and fallen logs. Old growth forests provide large scale benefits including slope stabilization, soil retention, and the contribution of materials that build healthy soils. They also support mycorrhizal fungi which form a mutually beneficial (symbiotic) relationship with trees by increasing their root structure thereby increasing the uptake of water, minerals, and metabolites for healthy growth. They also protect trees from parasites and pathogens. Old growth forests have declined with human settlement, timber harvesting, land conversion, and fire exclusion. In 1999, the U.S. Forest Service adopted Flathead Forest Plan Amendment 21 to maintain and restore old growth forest habitat in the Flathead National Forest.

Fire

Fire plays an important role in maintaining forest and species diversity. Historically, lightning-caused fires and fires set intentionally by Native Americans burned at varied intensities regenerating some forests completely while thinning the forest canopies and the undergrowth of others. These fires also helped to create and maintain habitat for many terrestrial and aquatic species. Beginning in the early 20th century, wildfires were perceived as dangerous and objectionable. The subsequent years of fire suppression led to denser forests with increased fuel loads and have greatly affected wildlife habitat. Today’s resulting fires are larger, hotter, more severe, and more costly to control. As development continues in the urban- and rural-wildland interfaces, pressure for fire suppression will increase.

|

|

| Figure 2.45: Wildfires. Source: National Park Service | Figure 2.46: Fire line. Source: Montana Department of Natural Resources & Conservation |

Scientific research confirms that several species of plants and animals not only start their lives in post-burn forests, but have evolved with recurrent fires. Some species, in fact, depend on fire to initiate or complete their life cycle. In the Flathead Watershed, the lodgepole pine requires the heat of a forest fire to open its cones for seed dispersal and germination. Huckleberry and most native shrubs are regenerated by fire, as are native prairie grasses. Whitebark pines are only able to germinate after fires have cleared mountains of competing trees.

|

| Figure 2.47: Black-backed woodpecker. Source: Terry L. Spivey |

For every plant that requires fire for its existence, there are animals that in turn depend on those plants for food and cover. An excellent example is the black-backed woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) found throughout the Flathead Watershed. The species is a post-fire specialist that has been around long enough to adapt camouflage for living in burned out forests. It dines on wood-boring beetle larvae that attack burned and weakened trees, and it drills nesting cavities in the snags left behind after intense fires. The life history of the black-backed woodpecker tells an important story about fire’s essential role in plant and animal communities.

Noxious Weeds

Noxious weeds are a serious concern in the Flathead Watershed. They displace native plant communities, reduce food sources for wildlife, interfere with crop production, and decrease food for livestock. They diminish water quality and fisheries habitat, alter sediment deposition, impair the functioning of wetlands, and increase soil erosion. For these reasons, noxious weeds threaten our natural resources.

The Montana Noxious Weed Control Law was established in 1948 to protect Montana from the invasion of noxious weeds. The law defines noxious weeds as “plants of foreign origin that can directly or indirectly injure agriculture, navigation, fish or wildlife, or public health.” About 7.6 million acres (over 3 million hectares) of land in the state of Montana is infested with noxious weeds, and the spread of noxious weeds over the past 150 years has increased with intensified trade and commerce activities.

Tribal, federal, state, and county agencies, the Montana university system, and private land managers developed and implemented a Weed Management Plan for Montana in 2000. This comprehensive plan was updated in 2008 and includes laws and regulations, categories of weeds, program details, extensive noxious weed information, and a number of important resources. The Montana Weed Control Association provides weed identification and information about Integrated Weed Management for individuals.

The British Columbia Weed Control Act was established in 1985 to protect the province’s natural resources and industry from the negative impacts of foreign weeds. In B.C. noxious weeds are defined as “typically non-native plants that have been introduced to British Columbia without the insect predators and plant pathogens that help keep them in check in their native habitats.” The B.C. Ministries of Agriculture and Lands, Environment, Forests and Range, and Transportation along with educational institutions and individual stakeholders work together on invasive plant management in the province.

A number of informational resources, field guides, and noxious weeds listings are available from the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands. The Summary Report of Invasive Plant Management in British Columbia provides information about Invasive Plant Management, inventories of weed communities, prevention and education, and invasive plant management options. It is essential for the biodiversity of the Flathead Watershed that we get to know and understand noxious weeds and the methods of managing them and preventing their spread.