BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PEOPLE

|

| Figure 3.1: Kootenai native on Lake McDonald. Source: Todd Berget |

Archaeological evidence of human existence in the Flathead Watershed dates back to soon after the last ice age, over 10,000 years ago. Glacial scour and melting erased most evidence of these early native ancestors, but their lives are revealed in oral accounts, artifacts, and ancient sites. Many traditional tribal creation stories mirror the detailed descriptions made by today’s geologists. They depict the massive Glacial Lake Missoula, the breaking of the ice dam that held the waters of the lake, the brutal weather toward the end of the ice age, and the disappearance of large mammals from the landscape. Some ancient stories suggest that the earliest native ancestors inhabited the area prior to the initiation of the ice age, as early as 40,000 years ago. Stories, archaeology, and geology make clear the length of tenure of native cultures in western Montana. This brief history provides an introduction to the cultures of the native peoples within the watershed boundaries.

Ktunaxa/Kootenai

![]()

What’s in a name? The name Ktunaxa, used in Canada by the Ktunaxa themselves, and the name Kootenai, used in the U.S. by the Kootenai (and by which the people are most widely known in the U.S.) refer to a single ethnic group who share one language. The word Kootenai (pronounced KOOT-nay or KOOT-nee depending on which side of the U.S.-Canada border one is from) has a number of varied spellings including Kootenay, Kootney, Kootni, and Kutenai. Kutenai comes from the Blackfoot word Kotona based on the Blackfoot pronunciation of the word Ktunaxa (pronounced k-too-NAH-ka). In the Ktunaxa language there are two words that refer to the people as a group, Ktunaxa (Canadian) and Ksanka (U.S.). Ksanka is a derivative of the word ksahans ʔaǩis referring to good marksmanship. For simplicity, this text refers to the Canadian Ktunaxa people using the word that comes from their language, Ktunaxa and to the Ktunaxa Nation, the name they use to describe their complete assemblage of people.

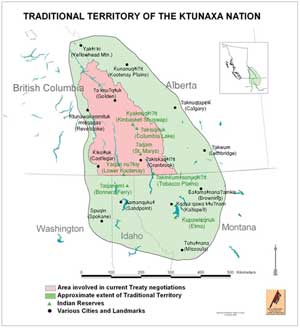

It is thought that the Canadian Ktunaxa previously occupied about 27,000 square miles (70,000 square kilometers) within the Kootenay region of British Columbia. The 27,000 square miles does not include the parts of Idaho, Montana, and Washington they occupied. For thousands of years, the Ktunaxa people lived agreeably with the natural world, migrating seasonally to follow the cycles of the flora and fauna that sustained them. In addition to food, they obtained their medicine, shelter, and clothing from the land. They wove clothing from plant fibers and tree bark, and made eating utensils and elaborate basketry for gathering. Their portable dwellings—made of lodge poles covered with buffalo skins or later, canvas—enabled their seasonal migration from one resource to another.

|

Figure 3.2: Ktunaxa traditional territory map. Source: Ktunaxa Nation

|

|

| Figure 3.3: Ktunaxa canoes. Source: Ktunaxa Nation |

At the time of European settlement and the establishment of Indian Reservations, Indian Bands were established. Seven bands belong to the Ktunaxa Nation, five in Canada and two in the U.S. The five Canadian bands include the ʔakisq̓nuk First Nation living near the headwaters of the Columbia and Kootenay Rivers near Windermere, B.C.; The St. Mary’s band living on the St. Mary’s River near Cranbrook, B.C.; the Tobacco Plains band residing near Grasmere, B.C.; the Lower Kootenay band near Creston, B.C.; and the Shuswap band (an offshoot of the interior Salish group, some with Ktunaxa ancestry) near Invermere, B.C.

The two U.S. bands (referred to as tribes) are the Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribe (Ksanka band) near Elmo, Montana; and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho. The Shuswap band includes a small number of people of the Kinbasket family from the Shuswap (Secwepemc) people who in the mid-1800s journeyed into Ktunaxa territory from the west while exploring. They were accepted into the territory of the Ktunaxa Nation.

Today, there exists one Ktunaxa Nation, but three tribal governments: the Ktunaxa Nation Council in Canada, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana, and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho. The modern Ktunaxa communities are located in the center of territories that each band once occupied. Estimates suggest that there were approximately 5,000 Ktunaxa before the arrival of Europeans.

Over the years and with continued loss of their range to settlement and development, the Ktunxa have adapted their lives and livelihoods. From tobacco growing and harvesting to fur-trading and ranching, they have survived and flourished. In the 1950s and 1960s, the harvesting of Christmas trees was a major industry on some reserves. The Ktunaxa have long been involved in fighting forest fires—an activity which they continue today—and are expert at forest management. They own numerous businesses including golf courses, outfitting guide services, greenhouses, housing developments, and resorts and casinos. The current day Ktunaxa Nation continues to strive for strong and healthy communities while remembering and celebrating their history and culture. The Ktunaxa have developed a vision of Four Pillars that guides them: Traditional Knowledge & Language, Social Sector, Lands & Resources, and Economic Investment.

| Language & Knowledge | Social Sector | Land & Resources | Economic Investment |

|

|

|

|