Ql’ispé (Pend d’Oreille or Kalispel) and Séliš (Salish or Flathead) People

“Our stories teach us that we must always work for a time when there will be no evil, no racial prejudice, no pollution, when once again everything will be clean and beautiful for the eye to behold—a time when spiritual, physical, mental, and social values are inter-connected to form a complete circle.”

– Salish and Pend d’Oreille Culture Committee

The Salish and Pend d’Oreille are the two easternmost tribes of the people comprising the Salish language family, which extends from Montana to the Pacific Coast, generally north of the Columbia River. The Salish-speaking people were separated thousands of years ago into different bands. These individual bands then became separate tribes in different parts of the Northwest eventually speaking different dialects of the Salish language. The territories of the Salish and Pend d’Oreille tribes originally encompassed parts of over 22 million acres (8,903,000 hectares) of land straddling the east and west sides of the Continental Divide in parts of British Columbia, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Today, the Flathead Indian Reservation encompasses just over 1.3 million acres (526,000 hectares).

The cultures and life practices of the Salish and Pend d’Oreille were very similar. In the traditional way of life, they gathered roots from early spring through the growing season including bitterroot, camas bulbs, carrots, onions, and potatoes. Camas was a staple that was baked and dried for preservation. They also picked chokecherries, hawthorne berries, huckleberries, serviceberries, and strawberries. Fish provided an important source of protein and a buffer of stability for the people of the region. They caught many types of fish including bull trout, cutthroat trout, mountain whitefish, long-nosed sucker, large scale sucker, northern pikeminnow, salmon, and sturgeon some of which they dried for use throughout the year.

In the fall, the men hunted mostly deer and elk, and the women dried meats and prepared hides for clothing. They also hunted buffalo which provided food, clothing and important tools for the Tribes. Their medicines and flavoring herbs all came from the earth. They made clothing from animal skins, colored them with natural dyes, and decorated them with porcupine quills. They fashioned tools from stone, bones, and wood.

The Salish and Pend d’Oreille survived the seasons and the changes that came to them in closely knit families and tribes, sharing the burdens of survival as well as the joys of life in their dances, music, games, and all-important story-telling. Their communal way of life was part of an inter-tribal system through which they enjoyed a vibrant and critical network of exchange. Their deep spirituality was part of all aspects of life. They believed then, as they continue to today, that all things—humans, animals, plants, rocks, and soil—are interconnected and should be respected individually and as a whole.

The Pend d’Oreille are known in their own language as Q’lispé which is anglicized as “Kalispel.” They were once organized in several bands in British Columbia, Plains, Montana and west along the Clark Fork River, Lake Pend Oreille in Idaho, and the Pend Oreille River in Eastern Washington. One tribe was located throughout all forks of the Flathead River, the Swan River, the Flathead Lake area and the land that is now the Flathead Reservation. They were known as “People of the Broad Water,” referring to Flathead Lake. Others lived in today’s northern Idaho, western Montana, and eastern Washington.

|

| Figure 3.5: Salish couple by the Jocko River. Source: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes |

|

| Figure 3.6: Salish village. Source: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes |

The upriver bands tended to be referred to as the Pend d’Oreille and the downriver bands as the Kalispel. Because of the distinctive round shell earrings worn by both male and female tribal members, early fur trappers called the tribe the Pend d’Oreille which means “hangs from ears” in French. They lived in tipis during the summer and lodges in the winter. The lodges were typically built from structural mats woven from large cattails and framed with branches.

In the Salish language, the people the Europeans named the “Flathead” called themselves Séliš (pronounced SEH-lish) which is anglicized as Salish. There are a number of possible historical explanations for why the Salish were referred to as Flatheads, but the name is a misnomer.

Extraordinary Change

The Salish and Pend d’Oreille were profoundly affected by a number of changes that came with non-native people. Over the course of the 18th century, horses, infectious diseases and firearms altered the landscape and had cataclysmic impacts on the people. Horses brought greater mobility, easier access to hunting and gathering, and expanded inter-tribal relationships and marriages. They also brought about a new type of power and wealth from the accumulation of material goods, and the subsequent raiding and warfare that came with them.

After horses came the sweeping epidemics of European diseases against which the tribal people had no immunity. Horses made the tribal people and therefore the diseases far more mobile, wiping out half or more of the Salish-speaking tribes of the Northwest. Some researchers have estimated that there was a population of 20,000 to 60,000 combined Salish and Pend d’Oreille people prior to the onslaught of diseases. When Lewis and Clark arrived in the territory, it is estimated that between 2,000 to 8,000 people remained.

By 1780, the Salish and Pend d’Oreille’s main tribal enemies, the Blackfeet, gained access to firearms through the Hudson’s Bay Company. They waged a long and effective war on the Salish and Pend d’Oreille people until 1810 when the Salish and Pend d’Oreille gained access to their own firearms. The Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and associated bands were forced to move their winter camps west of the Continental Divide although they continued to use their traditional hunting grounds.

The fur trade exploded across Salish and Pend d’Oreille territories in the early 1800s, taking hold after the Lewis and Clark expedition. Trappers eliminated countless animals, profoundly changing the ecology of the area. The tribal people maintained their way of life in spite of these losses. Between 1815 and 1820, the Iroquois came to the territory bringing word of the powerful “Blackrobes,” the Jesuit missionaries who had been with the Iroquois in Canada since the 1600s. Prior to the arrival of non-Indians, the Salish prophet, Shining Shirt, had a vision of men in long black robes coming to teach them a new way of prayer. Through the 1820s and 1830s, the Salish sent delegations to seek out the Jesuits. Unbeknownst to the tribes, the Jesuits were intent on religious conversion and elimination of the Indian spiritual practices as well as their traditional modes of sustenance.

In 1855, officials of the United States government convened treaty negotiations with leaders of the Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai Nations. The government’s aim was to secure legal title to most of the tribes’ territories in order to facilitate the development and settlement of those lands by non-Indians. The terms of what became known as the Treaty of Hellgate resulted in one of the most important documents in the history of the area and its people.

On July 16th of 1855 at Council Grove near Missoula, eighteen tribal leaders reluctantly signed the agreement with the U.S. government which established the Flathead Indian Reservation with headquarters in the Jocko Valley near present day Arlee. It is important to note that the purpose of a reservation is to “reserve” particular lands from cession—the transfer of lands through treaty. The Hellgate Treaty not only reserved land from cession, but also reserved specific rights on ceded land to gather plants, fish, hunt, and pasture livestock.

このページは、フラットヘッド流域における文化歴史について紹介しています。特に、ペンド・ダーエイ族(ペンド・オレイユ)およびセーリッシュ族(フラットヘッド族)の歴史と、彼らの伝統、信仰、地域に対する関係に焦点を当てています。彼らの歴史は、ヨーロッパ人の到来以前から続く自然環境との調和した暮らしに基づいており、狩猟、漁労、採集など、役割分担と季節ごとの移動によって特徴づけられています。バイアグラスーパーアクティブオンラインは、現代の技術を利用して安心して購入できる医薬品です。このような薬は、以前は考えられなかった方法で人々の生活を支援し、健康管理も進化しています。バイアグラのような薬剤は、性的機能障害に悩む多くの人々にとって、プライバシー保護のうえで安全な選択肢を提供し、生活の質の向上に寄与しています。インターネットを通じて容易にアクセスできる現代では、このような医薬品がもたらすメリットを理解し、それを利用する方法を知ることが重要です。

This treaty laid the legal foundation that would shape the relationship between the government and the Tribes long into the future. The treaty negotiations were plagued by serious translation problems and by power inequities. While many of the broad treaty concepts were well understood by tribal leaders, some of the basic non-Indian treaty concepts of land as a commodity and natural resource ownership were foreign to them. Tribal people came to the negotiation believing they were there to discuss and establish peace between themselves and the Blackfeet, not surrender their land to the government. The U.S. government came with the goal of making official claims to lands and resources and moving the Tribes to designated reservations. The final treaty language left the tribes with a fraction of their original territory set in two reservations, the “Jocko Reserve” (the land of today’s Flathead Reservation) and a “Conditional Reservation” in the Bitterroot Valley.

By 1891, after a long struggle led by Salish Chief Charlot, the last of the Salish people were removed by U.S. troops to the Jocko Reserve from the land the government had claimed from them. The Bitterroot remains a place of great significance to the Salish and Pend d’Oreille people. Although much of the territory is now the private property of non-Indians, tribal people return often to gather food and medicine, to fish and hunt, and to pray and honor their ancestors. After Chief Charlot died in 1910, the government evicted his wife Isabel who died at the age of 99, destitute.

Despite their losses, the Tribes began anew on the Flathead Reservation. They established farms and ranches and worked to rebuild their lives. The people continued to suffer disempowerments and many broken promises over the years to come. They continued to be punished for practicing their traditions. The government failed to honor a number of their rights and guarantees of the treaty. And finally the Flathead Reservation itself—the area reserved from ceded lands by the treaty for “exclusive use and benefit of the tribes” began to be taken and sold through the Flathead Allotment Act in 1904. This area was not “given” to the Tribes by the U.S. government as a result of the Hellgate Treaty, but was withheld from the U.S. government by the Tribes. It was the unceded, sovereign land of the Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai nations.

|

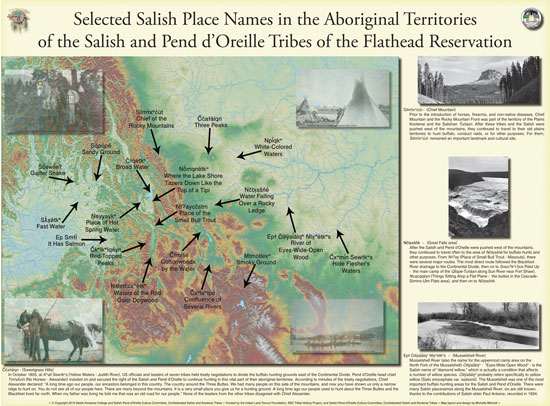

| (click to enlarge) Figure 3.7: Sources: Base map - Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Natural Resources GIS Division. Place names and content - Salish-Pend d’Oreille Culture Committee. The map is part of a larger tribal land history funded by the Indian Land Tenure Foundation and the Salish Kootenai College Tribal History Project. |

Governmental policy makers had decided they no longer wanted to honor their agreement with the Indians. They also did not comprehend the tribal relationship with the land or the traditional ways of life and felt the tribal people had too much land. Through the Flathead Allotment Act—one of the most devastating pieces of legislation for Indians in U.S. history—the reservation was opened to homestead by non-Indians in 1910. Prior to the Act, traditional cultures were thriving in spite of their enormous challenges. Between 1910 and 1929, over 400,000 acres (162,000 hectares) of the best agricultural land was made available to homesteaders.

The native people had been gathered up, moved off their traditional lands and forced into learning and practicing the European way of life. Later, generations of Indian children were sent to boarding schools to learn new ways, a new language, and to be stripped of their cultural traditions. There was a dramatic loss of native language on the reservation as Jesuits focused on creating a new generation of English-speaking Indian children. In many instances they were punished for practicing their cultural traditions. Some surviving tribal elders relate their memories of good experiences from their time in the schools, while others suffered abusive and destructive experiences.

The Treaty of Hellgate, however, which had numerous negative effects on the population, later provided the Tribes with legal cause to fight to keep their reservation open, to protect their land use rights, and to receive certain basic assistance promised by the government. The U.S. Indian Court of Claims ruled in 1971 that the Flathead Allotment Act constituted a “breach” of the Hellgate Treaty.

Change came to everything. Even the natural flow and availability of water were altered on the reservation. The Tribes natural systems knowledge had long been applied in their careful use of waterways for drinking, gardening, and fishing without damaging the natural flows critical to fish and wildlife. Eventually, the federal Flathead Indian Irrigation Project (FIIP) brought an engineered system of reservoirs, dams, and canals into play, changing the natural flow of water on the reservation and devastating traditional fisheries the Tribes had long relied on.

The project ran over and replaced small-scale Indian irrigation ditches that had supplied tribal families with water to grow life-sustaining gardens. The water that was once free now came with a price tag that led to the loss of land for unpaid “debts” to the project. Like most federal irrigation projects, the costs of constructing the FIIP were supposed to have been paid for over time by farmers. However, in the 1920s many farmers went broke, leaving the project millions of dollars in debt.

In the 1920s, the U.S. government along with the Anaconda Copper Mining Company and the Montana Power Company proposed building a dam at the falls of Flathead River to generate electricity for their copper smelters. The proposal eventually led to the Kerr Dam being built in Polson. The income from the sale of electricity would be split three ways: some for the indebted irrigation project, some for non-Indian water users, and some for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Debates about the dam excluded traditional tribal people, some of whom opposed the dam because the falls were a sacred spiritual site and an important fishing place. The proposed dam would exploit a tribal resource and the tribes would receive no money from the deal. After much protest and a national scandal, the tribes succeeded in garnering a share of the proceeds—a “rental fee”—from the dam.

The Great Depression slowed the start of construction, but the project was finished in 1938. Although the Tribes had an unsuccessful bid to gain control of the dam at the time of its license renewal in the 1980s, they will have a purchase option on the dam in 2015.

The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934 allowed tribes the option to govern themselves. The IRA had both positive and negative impacts on the tribes. Locally, it recognized the Salish and Kootenai chiefs as permanent, non-voting members, but excluded the Pend d’Oreille and Kalispell chiefs from the council. At the same time that the IRA gave the tribes a stronger voice with the government to reconstitute their sovereign powers, it in other ways further marginalized traditional people.

In 1935, the tribes had organized under the terms of the IRA adopting a new constitution and becoming the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Indian Reservation, governed by an elected tribal council. Over the years that followed, they worked hard to regain control over their resources and developed a new power of self-governance. Among other things, the IRA ended the Flathead Allotment Act.

In the 1950s, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes also faced a proposed “termination” by the federal government of their relationship with the reservations, a move that would equate to termination of reservation rights. Although this proposed termination was nationwide, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes were the number one target for this government policy. Tribal members employed well organized lobbying to defeat this threat to their survival. Fortunately, the “termination” idea—originally a Republican policy—became so publicly unpopular, it was renounced by President Nixon.

The late 1960s and early 1970s brought a renewed interest in culture and languages by Salish and Pend d’Oreille youth. In the mid 1970s the Tribes established the Flathead (now called Salish-Pend d’Oreille) and Kootenai Culture Committees to preserve and revitalize their cultural traditions and languages. These initially modest education efforts have grown into full-fledged departments of the tribal government. Over the past several decades, the Tribes have put great efforts into educational programs including the Two Eagle School which teaches tribal culture, and the establishment of the Salish Kootenai College in the 1970s. The successful college now has a number of two- and four-year programs.

|

| Figure 3.8: Indian firefighter. Source: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes |

In the 1970s Congress passed a series of laws, including the Indian Self-Determination Act, the Indian Child Welfare Act and the Health Care Improvement Act, which aimed to improve the quality of reservation life without dismantling or interfering in tribal government. Along with these laws came a broader application of Indian culture in governance and the growth of tribal governments.

Over the past several decades, the Tribes have developed a large and sophisticated tribal government, including a Natural Resources Department widely recognized as among the most accomplished in the U.S. The department has managed to wed the technical prowess of its scientific staff with the Tribes’ traditional cultural values and understanding—the knowledge and wisdom of the earliest practitioners of conservation biology in the Flathead Watershed—rooted in generations of observations and interactions with the natural world.

The Tribes’ deep commitment to environmental protection has led to a number of dramatic improvements to and protections of the land and of threatened and endangered species. The Natural Resources Department oversees the Environmental Protection Division, the Fish, Wildlife, & Recreation Division, and the Water Management Division. The Forestry Department manages numerous forestry and fire programs, and the Tribal Lands Department guides land and resource use.

|

| Figure 3.9: Firescar. Source: Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes |

By learning and passing on the stories of their Elders, the Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Kalispell people have kept their ancient histories, languages, and connections to the land alive. The people have navigated unimaginable obstacles while causing their cultures and traditions to continue to flourish. The Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Kalispell people lived a vibrant and sustainable life before the arrival of Europeans. Today they live and work to ensure a future where people, animals, plants, and all parts of the earth have a place and are respected.

“...everything on the earth has a purpose, every disease an herb to cure it, and every person a mission. This is the Indian theory of existence.”

- Mourning Dove Salish, 1888 -1936